An Inventor’s Quest for the NHL Pt. 5

Steps and Missteps

This series follows my attempt to develop a product that I dream of getting into the NHL. Previously on the Quest: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

Not every idea I’ve had during the development of my prototype has been a good one.

One of those missteps came as I was figuring out how to orient the Kevlar thread in my design. Remember, I’m using Kevlar thread because my basic idea is that a flexible net-like structure will be more efficient than a rigid cage.

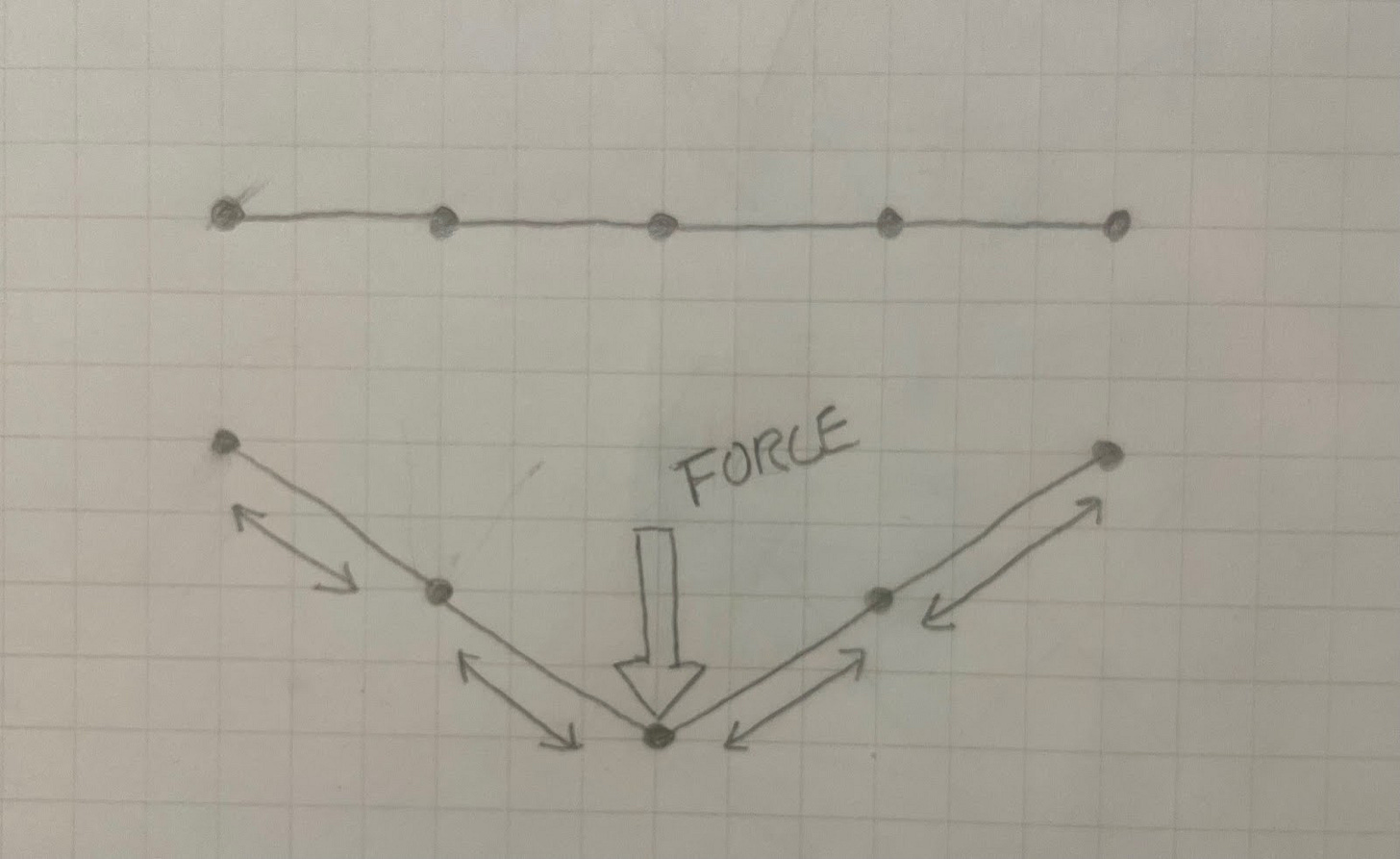

I’ve already talked about one benefit of a net -- that it’s loaded entirely in tension. A second benefit is that all of the strings in a net work together. When you push on a single string in a net, all of its neighbors start stretching too.

The more a string stretches, the more it resists. Just like a spring. So with a net, instead of just pushing on one spring, you’re essentially pushing on a mattress full of springs, where neighboring springs pitch in to help resist your weight.

Of course, I couldn’t use a regular net because there’s a goalie’s face in the way. I needed something that bowed out around that obstacle. But that necessary convexity presented a problem. If you push down on a hypothetical convex net, the connecting strings get shorter. And a string doesn’t really resist getting shorter.

So how to tie the strings together so that they act like a net despite the convexity? In other words, how could I make it so that when one string stretches, they all stretch?

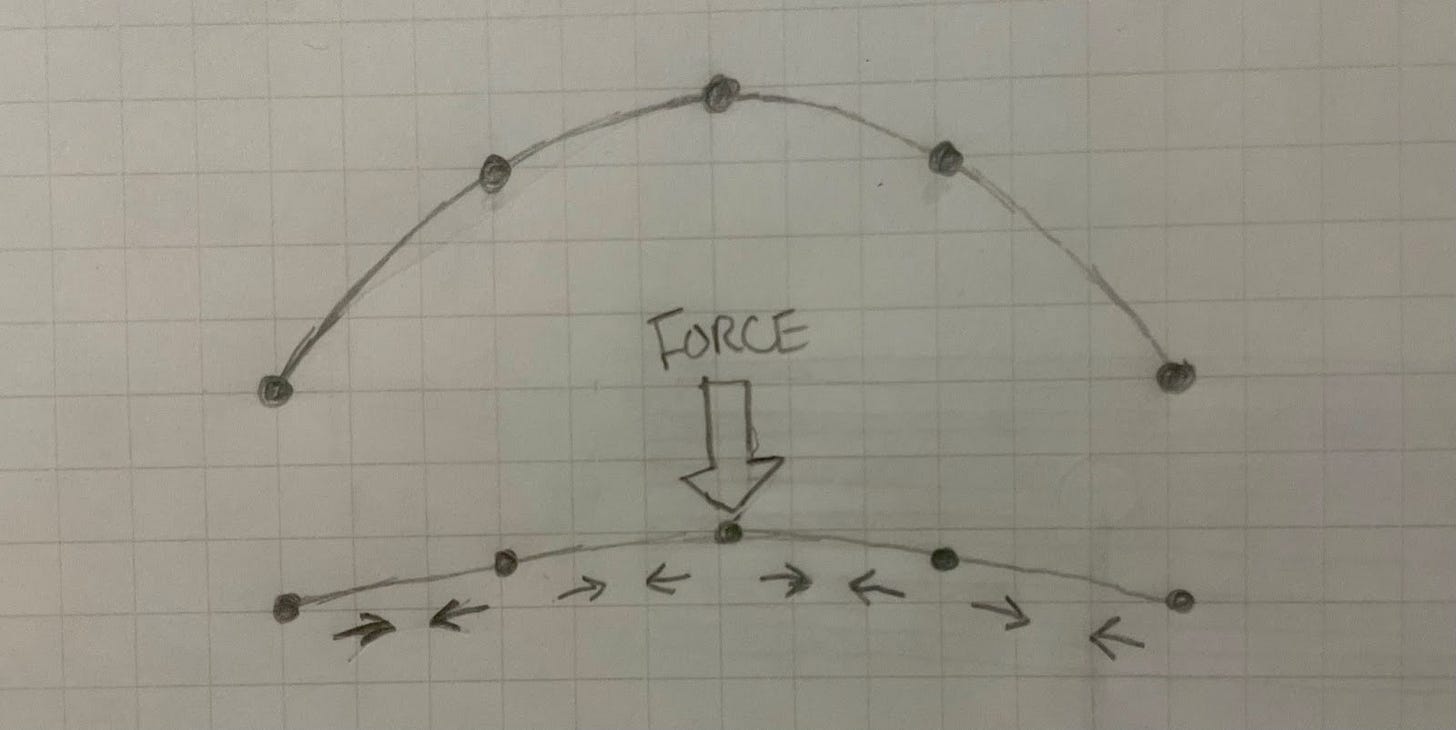

The answer is to tie the strings together with something rigid -- with a connection that can push and pull, the picture looks different than it did before.

Eureka! A convex net.

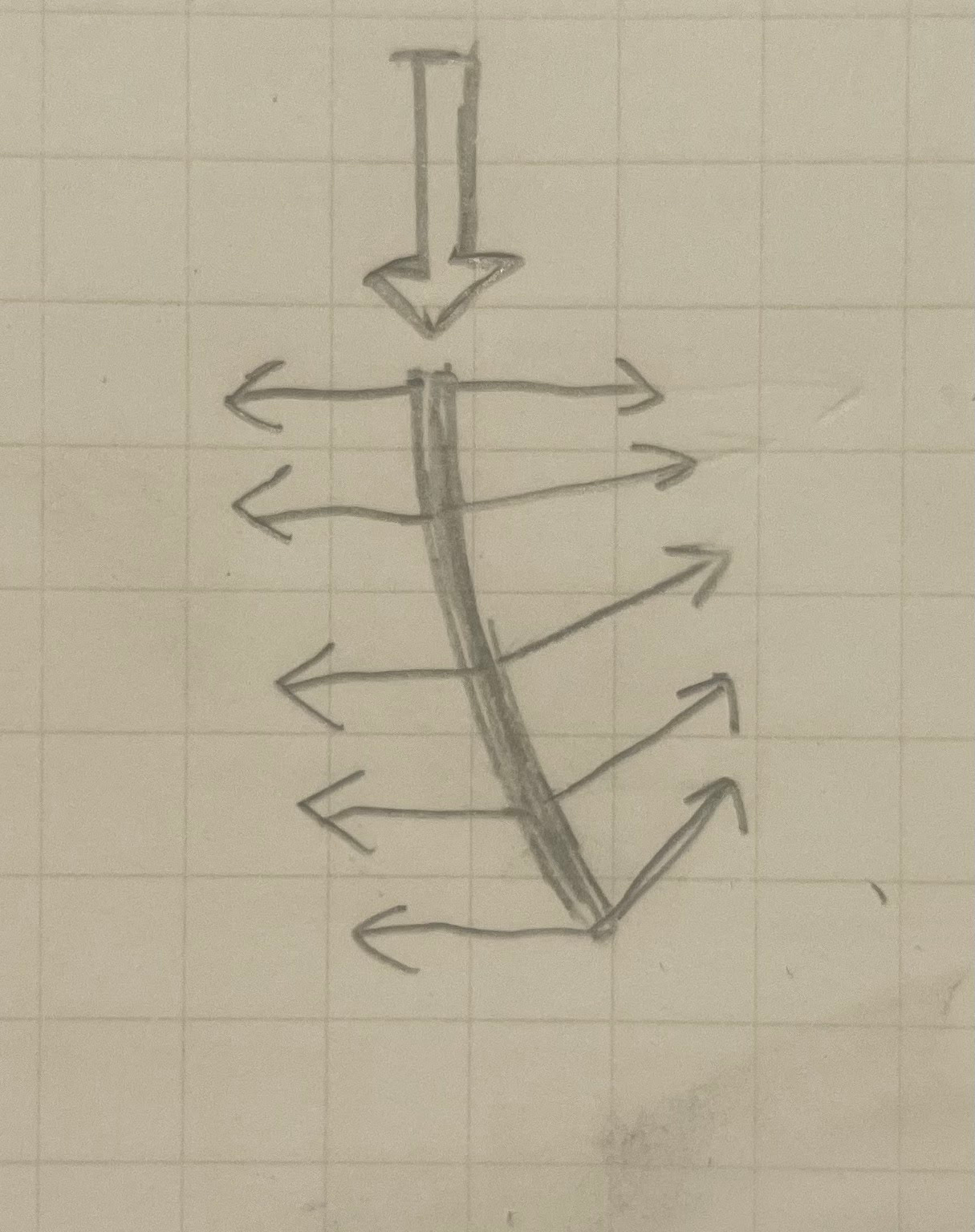

Up to this point, I was doing well, but here’s where I had a few missteps. I started out trying to make a straightforward net with the strings oriented in a grid.

As you can see, a good amount of the strings were angled up. Essentially, I created convexity in a different direction than I had before. Meaning that, if the crossbar (the bar across the middle of the face) was pushed down, the strings would get shorter and not resist -- just like the hypothetical convex net from earlier.

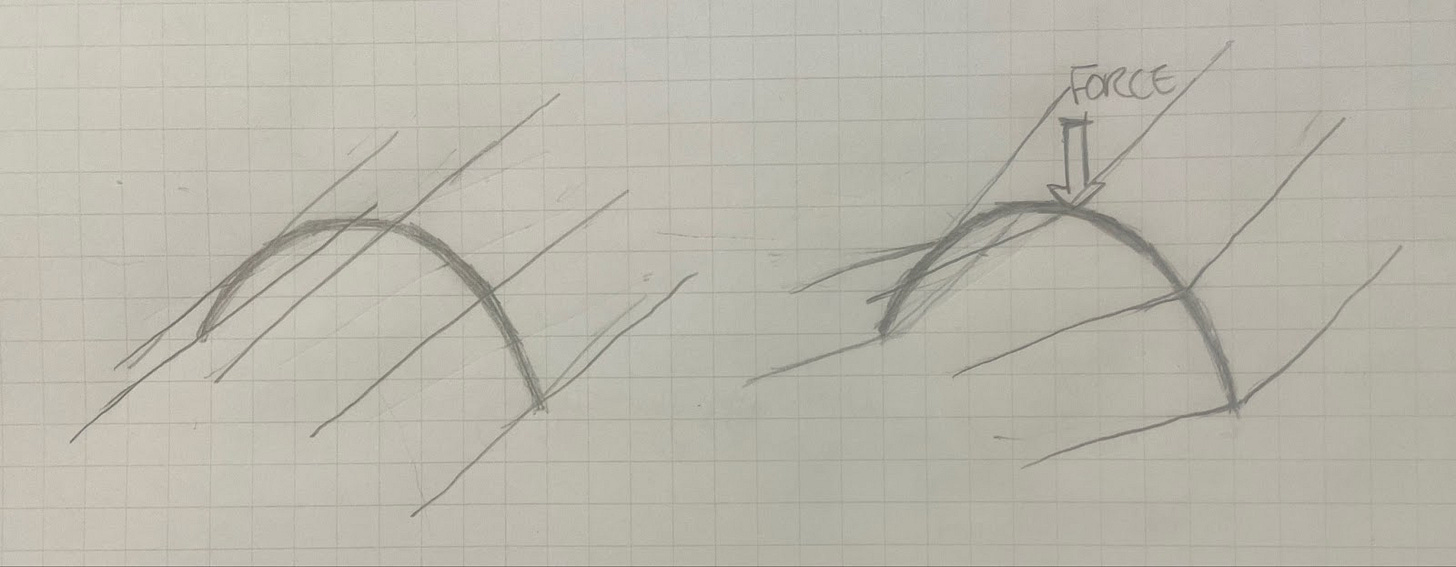

What to do? I tried orienting the crossbar like a frowny face and fanning the strings out.

My idea was to make a hinge of sorts. A short string is stiffer than a long string, just like a short spring is stiffer than a long one. So the ends of the crossbar, which were connected to the frame with short strings, wouldn’t move as much as the middle of the crossbar, which were connected with longer strings. That difference in movement would create a hinge-like movement.

My thought was that forcing the crossbar to hinge over would get more strings involved.

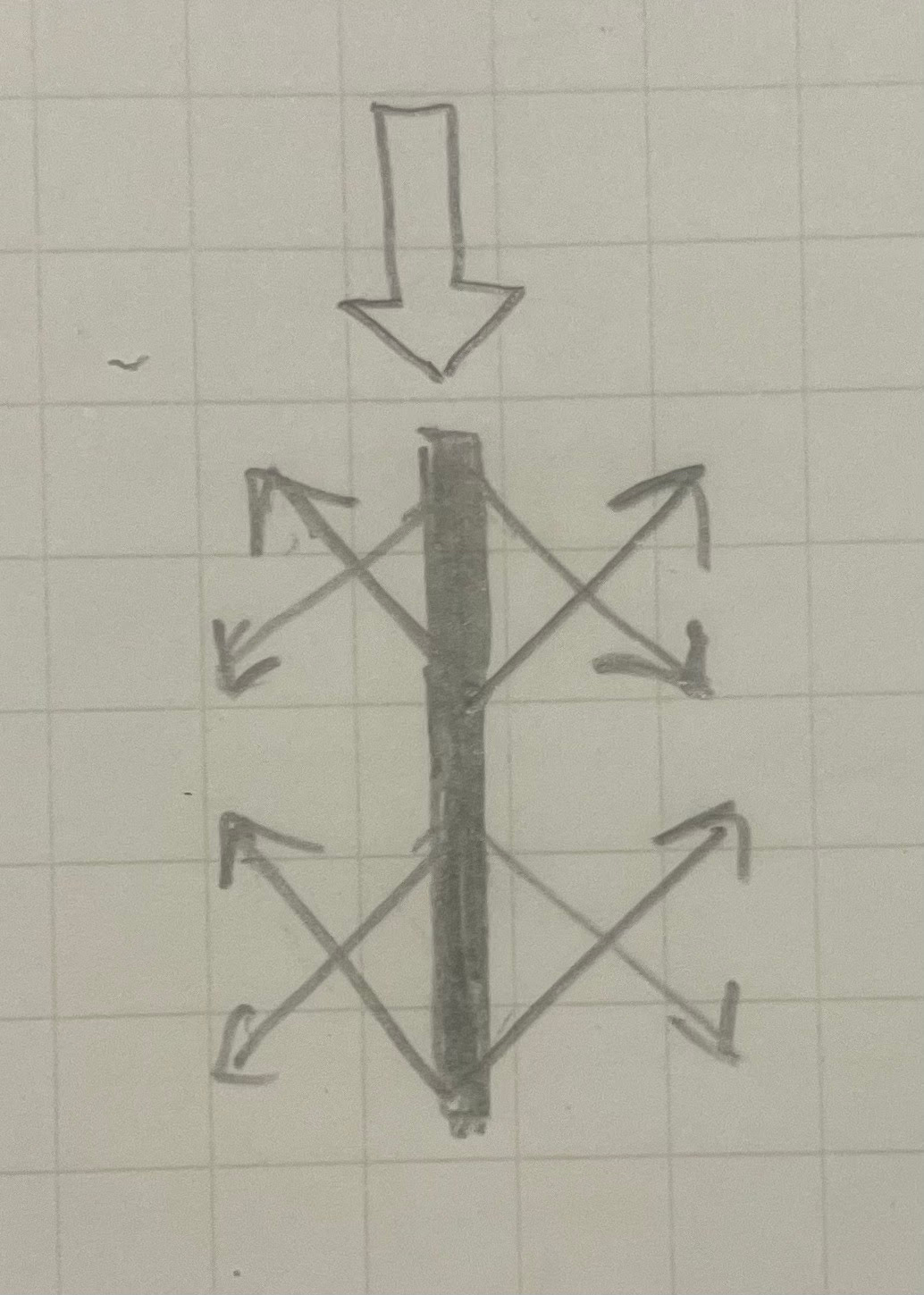

A reasonable theory. But when I mocked it up and tested it (by dropping pucks/weights on it from a height), the results were not great. The structure was a bit too flexible.

Why? I had gotten tunnel vision on trying to get more strings involved with the movement of the crossbar, and had forgotten the basics.

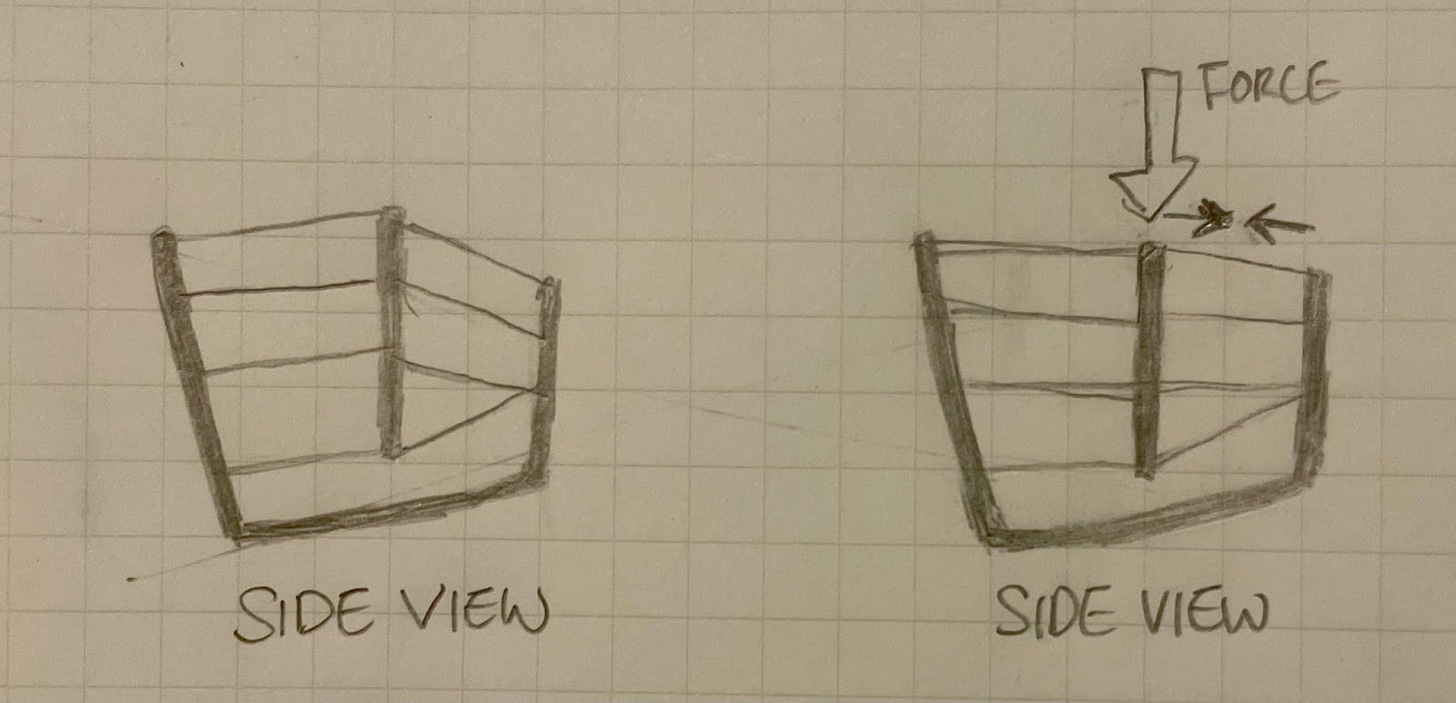

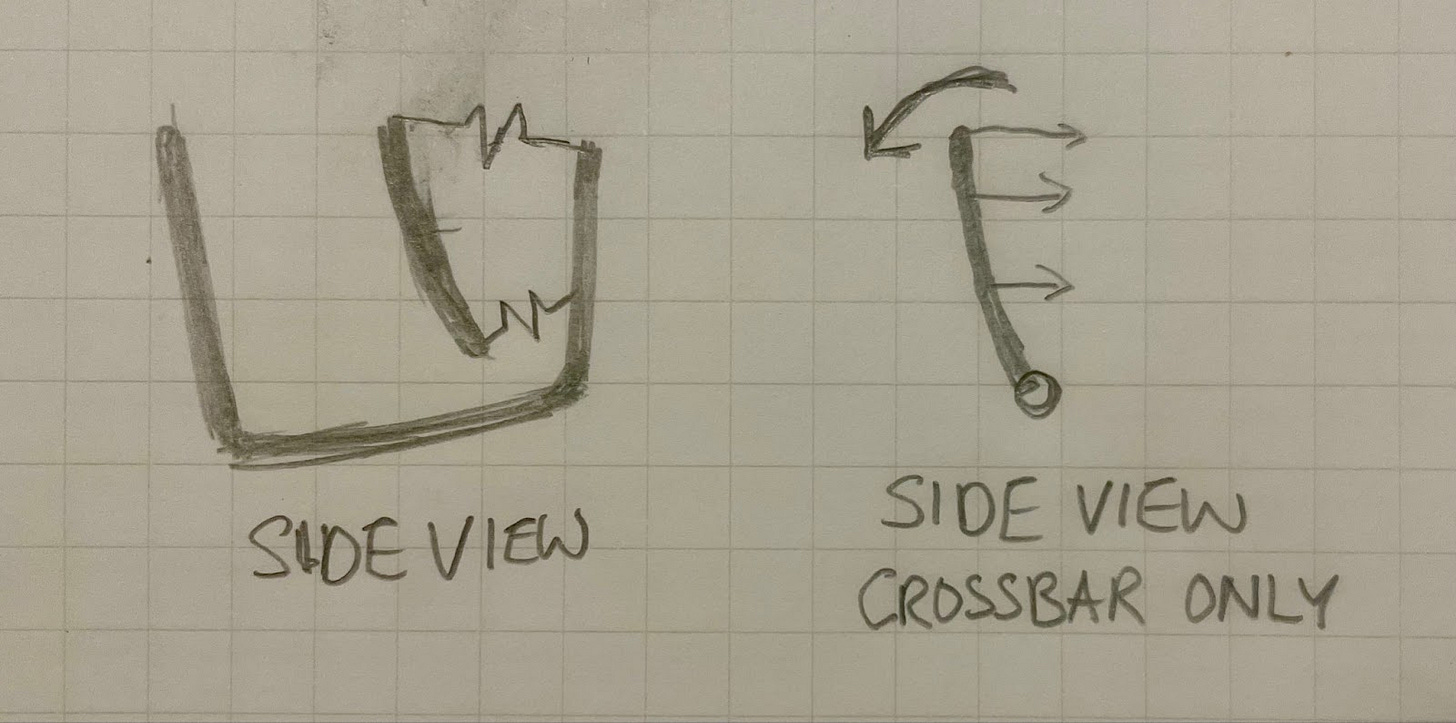

Let’s do a free body diagram from a side view.

That’s awful! Almost none of the strings are positioned in a way to counteract the force; they’re all perpendicular.

I adjusted the string pattern to remedy that by making Xs above and below the crossbar.

It’s a small change but it’s made a world of difference. The design feels orders of magnitude more stable. Another small step towards a functional product.

Thanks for reading.